I recently finished Poor Charlie’s Almanack, a collection of eleven talks by Charlie Munger. When Stripe Press published a brand new edition of it with their usual beautiful type setting and cover design, I couldn’t resist.

For those unfamiliar to Charlie, he is worth getting to know. While his notoriety stemmed from being one of the greatest investors of his generation, he was also a prolific speaker and writer, and was an advocate of cross-disciplinary thinking and application of mental models. He excelled in taking ideas from mathematics, philosophy, and psychology in order to think about the world in a new way.

In this month’s article, we’re going to be looking at one of the mental models I learned from Charlie and how it can help us as engineering leaders think, plan, and execute better by avoiding failure.

Death by optimism

Software engineering is tough. No matter how hard we try and how hard we plan, we always end up missing simple things which cause a whole bunch of problems down the line.

This can range from missing features and functionality (“how did we not think of that?”), to edge cases that we haven’t thought about (“how did we not see that coming?”), to poorly conceived rollouts and launches (“why didn’t we check this didn’t work in Italy?”).

There seems to be an ability to repeatedly stumble on the same simple mistakes that suggests this is just part of human nature. We spend so much time thinking about the big picture, focusing only on the happy path that we’re traveling down, that we tend to overlook stupid mistakes that then shoot us in the foot.

The question, therefore, is why?

Why is it that we make the same mistakes over and over again? After reading Poor Charlie’s Almanack, I’ve come to think that it’s because we apply mental models that are far too optimistic to our planning. As a result, because we typically rely on an optimistic outlook, we fail to consider what could go wrong.

Countless software projects in the last twenty years have significantly underestimated time and complexity, have not done enough QA, have not considered their rollouts carefully enough, and haven’t scrutinized their scope to ensure that key features were missing.

There’s clearly a core bug in our thinking, because humans would have solved these planning problems a very long time ago if it didn’t exist.

What is inversion?

If it is the case that thinking too optimistically is one of the reasons that we keep getting things wrong in software engineering, can we instead use a pessimistic mental model? The answer, I believe, is yes, and the solution lies in one of Charlie Munger’s models called inversion.

Inversion is one of the cross-disciplinary mental models that I mentioned above that Charlie mentioned often. He would use the inversion mental model in order to scrutinize investments before he made them. When it comes to planning projects, estimating scope, and especially rolling out changes, inverting the problem can expose the blind spots optimism leaves behind. The principle of inversion is highly applicable to us as engineers.

As Charlie says: “Invert, always invert.” This is the way that you can save yourself from disaster.

The origin of inversion comes from the 19th-century German mathematician Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi, who advocated for solving problems by approaching them backwards. Rather than trying to work something out directly, you assume the opposite and work toward a contradiction.

Munger adapts this into practical situations: to succeed at an outcome, you should invert it by thinking about what would have to happen for you to fail, and then completely avoid all of those things in order to succeed.

For example, if your goal is to keep your home clean, instead of thinking about what it means for it to be spotless, you can invert the problem by thinking about what it would mean for it to be disgusting, and then make sure you do everything possible to make it not disgusting.

It follows that for your home not to be disgusting, you would need to:

- Clean your dishes within 24 hours.

- Take out the bin when it’s full.

- Vacuum the floor once a week.

- Dust surfaces regularly.

- Do your laundry when the laundry bin is full.

- …and so on.

And it just turns out that by inverting the problem and then doing all the items above to avoid it being disgusting you arrive at the same outcome: you have a really clean house.

This is the beauty of inversion. Instead of asking yourself, “How do I succeed?” you ask, “How do I fail?” and then systematically avoid those failure modes.

Inversion for engineering teams

Engineering teams can greatly benefit from using the inversion approach when thinking about larger initiatives such as estimation, planning, and rollouts.

As we saw above, whenever we do these activities with default optimism—thinking about what would be nice to have and what we must try to achieve—we often forget the things we must avoid as part of that process, which is where the mistakes creep in.

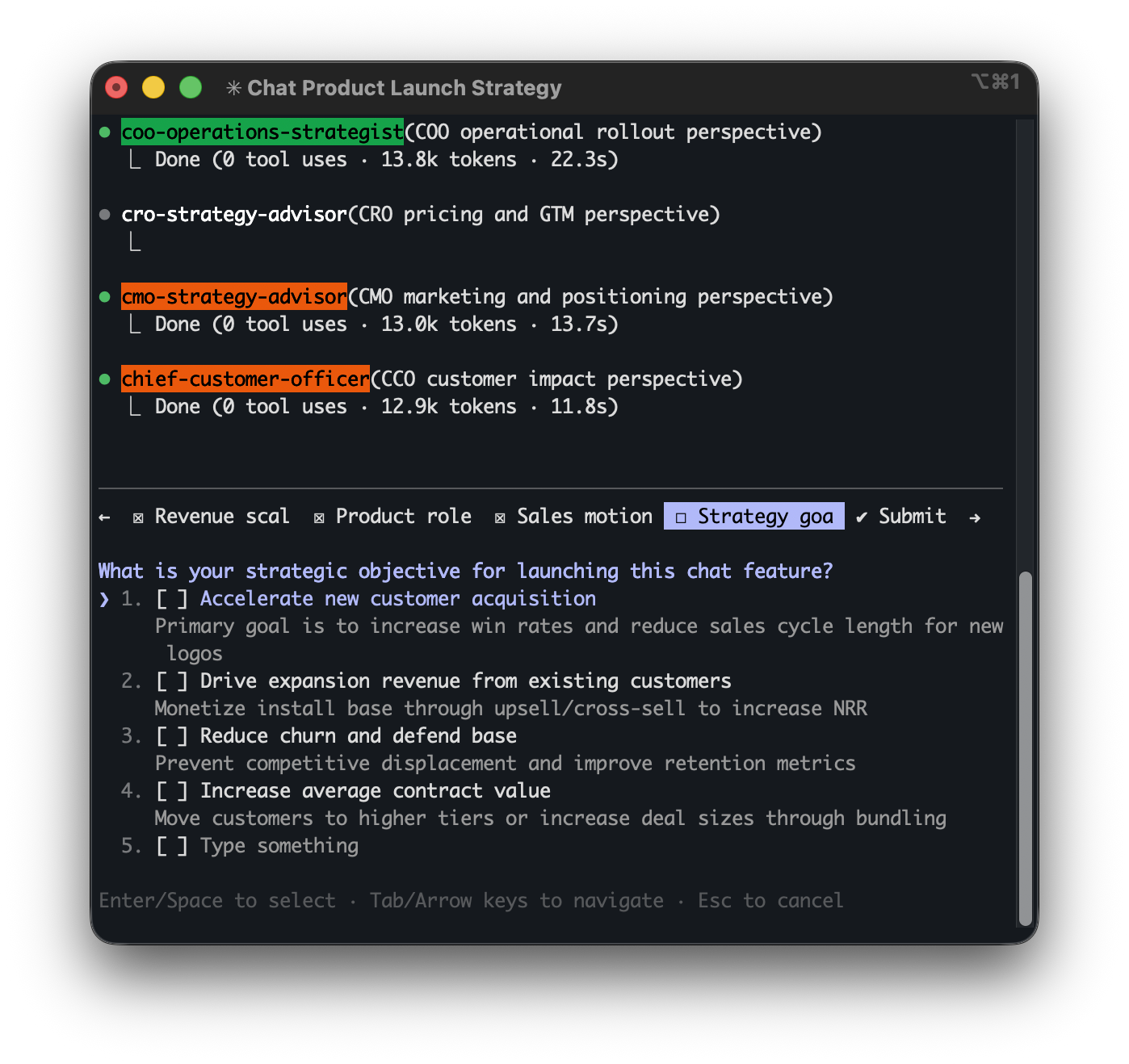

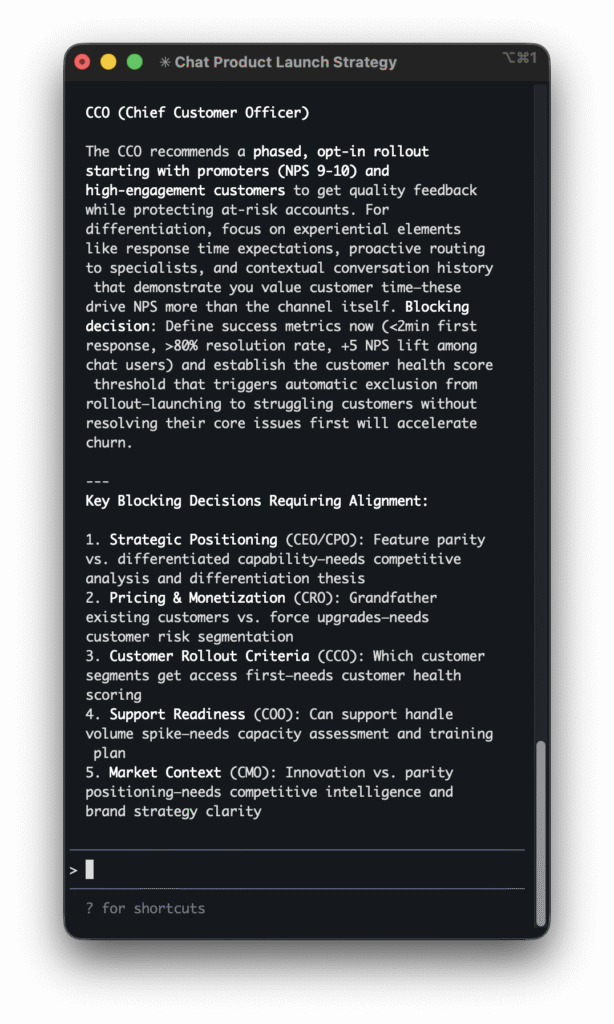

For example, if we are thinking of rolling out a new feature gradually to our clients, instead of leading our thinking with cohorting and the desire to launch to everyone as quickly as possible (i.e. goal oriented), we should think about what it would mean for the rollout to be a complete disaster, identify those factors, and completely avoid them. Doing so will ensure that we avoid edge cases in our thinking that we may have missed previously.

This is best explained by example.

Let’s imagine that you’ve just made a significant upgrade to part of your application and you’re thinking about how to roll it out. Instead of asking yourself how the rollout could be a success, you could invert the problem and ask yourself how the rollout could disastrously fail.

You identify that it would fail if:

- Bugs are present.

- Customers are unable to opt out if they don’t like the experience.

- Enterprise customers are caught off guard by the change and are not given adequate advance notice.

- Workflows take more clicks or scrolls or text inputs than the previous workflow that was upgraded.

- It looks worse, or is less intuitive, than the previous functionality that it replaced.

- It is slower than the previous workflow to render.

I’m sure there’s other examples that you can think of here too.

If you can take that list of reasons that the rollout could fail, and then systematically work to put protections in place so you avoid them, then it would follow that you would have a successful rollout.

Doing an inversion pass

I’d like to propose that the next time you do a significant piece of work, you do an inversion pass. It will help you systematically identify failure modes and build your defenses before you embark on whatever you’re about to do.

Below is a template that you can copy and edit for your own needs.

Setup

Before we get going, we need to work out who’s doing what.

- Begin by assigning roles. One person should be the facilitator who keeps time and the discussion flowing. There should also be somebody acting as a scribe that is able to capture the conversation.

- Then define the scope. Decide what it is that we’re trying to invert, which could be a feature rollout, an infrastructure change, or an architectural decision, etc.

- Make it clear that no idea is too pessimistic, and that today we are being paid to be cynics.

Inversion questions

With roles defined, work through these questions as a group.

The facilitator keeps the group moving and on time, and the scribe ensures that everything is captured. Questions that are in quotes are intended for the facilitator to ask the group.

- Catastrophic failure. “What would make this an absolute disaster?” If this was to cause a P1 incident, what could some of the likely root causes be? What kind of scenario would have happened in order for that to trigger? Which single component failure would cascade most dramatically?

- Silent degradation. “How could this fail without us knowing?” What metrics are we not monitoring that we should be? Which failure modes wouldn’t trigger our existing alerts? Where might we have blind spots in our observability and logging? What could degrade slowly enough that we wouldn’t notice until customers complained?

- Rollback. “What if we need to roll this back at 3am?” Can this change be reversed? How long would rollback take? Is there anything that’s irreversible? At what point does rolling back become more dangerous than rolling forward? What happens if none of this works?

- Load and scale. “What happens when real load exceeds our assumptions?” If you’ve currently estimated a certain load, what would break at 10x that load? Are there any resources that you have assumed will work properly that could go wrong? What kind of behavior exists in high traffic scenarios with extreme contention or queuing?

- Dependency failures. “What if everything that we depend on breaks?” List out all of the external services that you rely on, such as databases and APIs. For each of them, think about what could go wrong if they became slow or unavailable. Think about whether you should have retries or circuit breakers.

- Human error. “How could we break this ourselves?” Are there any operational steps that could be prone to human error? Do we have everything written down in playbooks in case whoever is on call doesn’t understand what to do, or are we missing documentation?

- Data integrity and security. “Is it possible for us to corrupt or lose data?” Have we thought about race conditions that could happen? Or have we assumed transactionality that doesn’t actually exist? What happens if we process the same event twice, or if we skip one event? How do we know if data becomes inconsistent? Are there any attack vectors that we need to think about? Which data are we exposing and to whom?

You may want to add or remove inversion questions depending on the kind of project that you’re doing.

Once you’ve captured your list, go through and mark each item as to whether it’s:

- A showstopper (which must be addressed before launch)

- A mitigation (which will need monitoring, fallbacks, or workarounds)

- An accepted situation of which we are understanding the risk and moving forward regardless.

When you’ve got to this point, you should have list of actions captured by your scribe that you go and work on, plus a documented inversion pass outcome that proves you have done this exercise. You can use this to generate a risk register, update your design docs, and expand your documentation.

Try it yourself

Sometimes being pessimistic is good.

Using the principle of inversion, you can identify gaps in your planning and thinking, which can make your projects better, safer, and more resilient.

In your next project, try out an inversion pass. Run the exercise on your own or do it with your team and see whether it helps you feel more confident about what you’re going to be doing next.

Additionally, think about inversion in your own life. If you were to apply the inversion principle to how you manage your finances or what you want to achieve next year, could it potentially help you to think about these goals in a new light? Perhaps it could increase your confidence in getting them done to a high standard.

Remember: invert, always invert. If it worked for Charlie, it works for me.