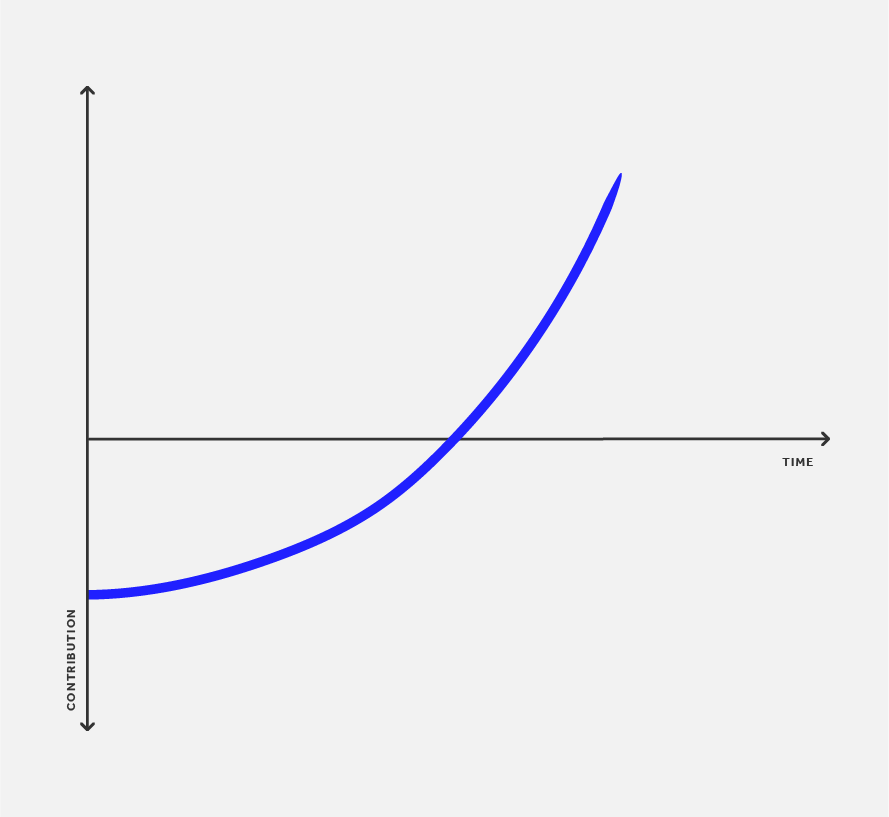

The curve

As a manager, your performance is going to be judged on your output. As we’ve explored in previous articles, you can measure the output of a manager as the output of their organisation plus the output of the organizations under their influence. How can you make sure that your staff are performing as well as they possibly can in an environment in which they can grow? Let’s talk about the contribution curve.

Your best individuals will contribute a significant amount to your department through impactful work and their positive network effect on others. Your least impactful individuals can be a drain on your department, and you need to make sure that you choose the right tactic for helping them improve as quickly as you can.

Below is a hypothetical example of an contribution curve for a talented graduate joining a company for the first time.

At the ends of the line you have net-negative and (currently maximal) net-positive contribution:

- Net-negative: A particular individual, for the input of their work over time, produces a net-negative output for the business. As horrible as it sounds, the organization would be producing more output if they weren’t there.

- Net-positive: A particular individual, for the input of their work over time, produces a net-positive output for the business. Some people produce more of a net-positive output than others, and you would hope that those people are rewarded fairly for doing so.

Three reasons

Clearly we want individuals to be as net-positive as they possibly can be. But why are people net-negative? Typically there are three reasons:

- Inexperience: The best case (if there has to be one). An individual needs education and mentorship to push through to being net-positive. This is a training problem.

- Poor placement: An individual is doing work that is either too challenging for them or they are unclear on how they should be effective in their role. This is a management problem.

- Poor performance: An individual is not performing well in their role, despite having the support that they need. This is a performance problem.

Let’s take a look at them individually.

Inexperience

Everyone is a net-negative contributor at some point. From a graduate engineer starting out in industry for the first time, to a senior engineer beginning a new job, we all will repeatedly find ourselves in positions where to be net-positive requires time and support from other people. For talented people with the right attitude, as managers, we should be looking to allocate as much resource as possible to getting them ramped up and productive.

One of the simplest examples of this progression is from a graduate engineer to a tenured senior engineer.

- A new graduate will be new to the industry and the company, so they will require support through training and mentorship in order to understand the technology being worked on, the business problems being solved, and the codebases and tools used to solve them. Their code will typically require a fair amount of checking whilst it is being written and also a higher level of scrutiny when it is being reviewed. They are net-negative because of the amount of time they require from others to get their work done.

- A tenured senior requires less support when developing new code, and is often doing so in such a way that will enable others in the future. Why? They know the business and the codebases well and create new features pretty quickly as a result, they also review a lot of code from others and are often paired with more junior staff from drawing designs on the whiteboard to pair programming, and they are net-positive and enable themselves and others to be successful.

For a talented and hard-working individual, both of these extremes in the contribution curve are completely normal places to be. The only fault that makes the graduate net-negative is that they are at the beginning of their career and they need time and support to become more expert. This is why this is a training problem. You need to be able to spot when people are in need of assistance and give them the resources that are required to move into being a net-positive contributor. You have a number of tools at your disposal to do this: assigning them a mentor, sending them on training courses, giving them books and online materials, and just making sure you’re on top of their career development and motivating them along the way.

It’s worth noting that it won’t always be those with less experience who find themselves in a net-negative situation. Even talented senior engineers will find themselves being net-negative when they start a new job, or when they change team to work on a different area of the application. The true measure of a good support structure is being able to accelerate engineers through to net-positive as quickly as possible.

Poor placement

Sometimes people can be hard working and talented but the particular project that they find themselves on just isn’t right for them. This can be for a multitude of reasons: they may not fully understand it, it may be in a programming language or framework that they find harder than others, or it may just be a project that is too challenging for their current level of experience.

This is a management problem, and you need to solve it. Depending on how your organization works, your teams may stay fairly static but your projects will change over time. One member of your staff may be extremely productive on a particular project only for the next one to leave them working on something that doesn’t best suit their skill set.

In an ideal world, your staff will tell you when they find themselves in this situation. However, in reality, they’re probably not going to say. It’s embarrassing to say that you’re struggling. Even worse, they might think that they will be punished for poor performance! Instead, as a manager, you need to build a close rapport with your staff so that you can sense when this is happening. Probe into how they feel about their current work, whether it motivates them, and how it plays to their strengths.

Also, try to encourage a culture where individuals can change teams easily without any awkward feelings about doing so. In the end it doesn’t really matter what team somebody is on, as long as they are productive. It shouldn’t be seen as a bad mark against a manager if one of their staff goes and works for another team. After all, everyone is contributing to the company regardless. Consider allowing staff to freely vote to move teams at the end of projects, or at the end of every quarter. If your headcount is quite restricted, why not introduce a matchmaking scheme where those that want to swap teams can as long as they find someone to swap with?

Poor performance

The worst one. Whereas a net-negative graduate engineer with a lot of potential will require time from others, the process and outcome is pleasurable: senior staff get to improve their mentorship skills and see another person grow.

A net-negative poor performer has a bigger blast radius for their net-negativity compared to the previous examples because they are a drain on collective morale as well as the time and attention of other staff. Their team mates will have to pick up their slack, which in turn makes them do a worse job because they are frustrated. They will be less willing to give up their time to the poor performer because of the drag that it causes. This is a performance problem that needs your attention.

When considering the overall output of a team, sometimes it can be improved by removing the poor performer altogether, which highlights the importance of your role as a manager. In the same way that the team would be frustrated if their manager had provided them with laptops from 2003 to do their work on, they will be frustrated that they have to work with a poor performer. As a manager you have allowed the poor performer to be part of their working environment, and they’ll be looking to you to sort that out.

Perhaps they can be moved on to another team with some clear goals for their performance improvement, whilst at the same time giving them a fresh start with new team mates. You cannot treat net-negative poor performers in the same way that you treat net-negative inexperienced engineers and hope that the team will somehow train them out of being poor. It won’t work that way: instead, you are showing that your bar is low for the quality of your staff, and others are being made to suffer because of it. Take ownership, have the hard conversation, and see where is their best chance to succeed in the organization.

In summary

You need to keep a close eye on how productive your staff are being: it can change over time with experience, the projects they are on, and their performance. Keep pushing everyone to be as net-positive in their contributions as possible, even if it means having some tricky conversations. Not everyone will be as skilled as you want, and not everyone will be on their ideal project. However, with careful balance of people on the right projects, you can gradually increase the net contribution of your teams, ensure that the next generation of engineers are learning their trade, and concurrently allow other staff to become excellent mentors.

Unfortunately, the poor performers are up to you to sort out. Sorry about that.

Pingback: Newsletter 50 – The Long Now | import digest