Once upon a time, in a galaxy far, far, away, when I first got into management, I had mistakenly assumed that progression up the org chart meant only managing other managers.

How I was totally wrong.

Individual contributor career progression grows in parallel with management career progression, and in large organizations that implement these dual tracks, you will see individual contributors with the same seniority as managers. And this goes all the way up to the top of the org chart.

For example, at large technology companies you’ll find Principal Engineers reporting to Directors and sometimes you’ll find Distinguished Engineers reporting to VPs. Each has a different skill set but the same seniority and scope.

When a manager oversees a broad organization, a mix of managers and individual contributors cascade downwards from them in the org chart, with each pair typically overseeing the same subsets of the entire department. If you’re wondering what kinds of things these senior individual contributors do and how they operate, then check out Will Larson’s post on Staff Engineer archetypes.

Progression up the managerial track therefore isn’t just about managing other managers: it’s also about managing senior individual contributors too. This makes senior management doubly challenging, because you need to be able to manage both roles effectively, and a new senior manager may now be managing individual contributors that have far, far surpassed them in their own craft.

The pertinent question is whether you should manage senior managers and senior individual contributors differently. After all, they have different roles and responsibilities, and so it would be natural to assume the way that you manage a Staff Engineer would be different than the way that you manage an Engineering Manager. Right?

Nope, that assumption would also be wrong. Sorry.

You don’t need special approaches for managing both roles. In fact, you can apply the same strategy to both, and not only does this simplify your approach, it actually encourages the best behaviors from both roles.

Let’s explore this in more detail.

Control at the Intersection

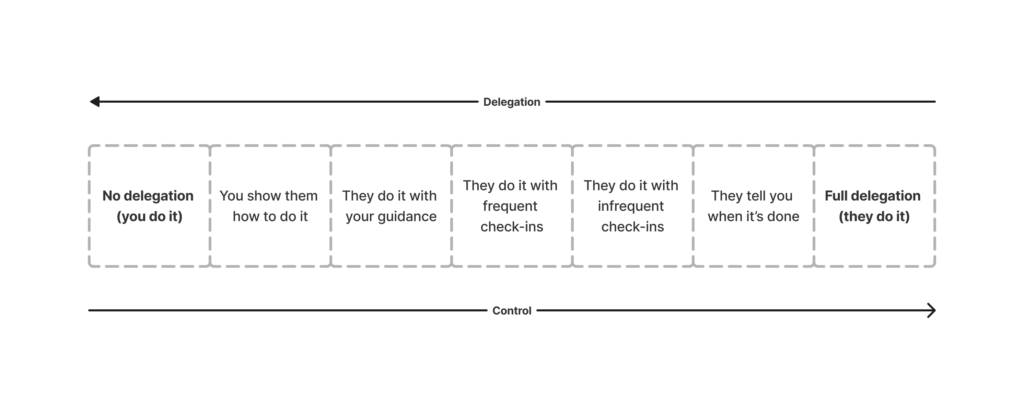

Previously in my writing we have covered delegation, which is one of those core Management 101 concepts that you need to get right from the beginning.

Delegation isn’t just about telling people what to do. It’s about the delegation of responsibility whilst maintaining accountability.

Delegation isn’t a Boolean choice either: it is a spectrum that you traverse depending on the competency match between the task and the person or team that is doing it. You may assert more control through hands-on involvement or less control through delegation.

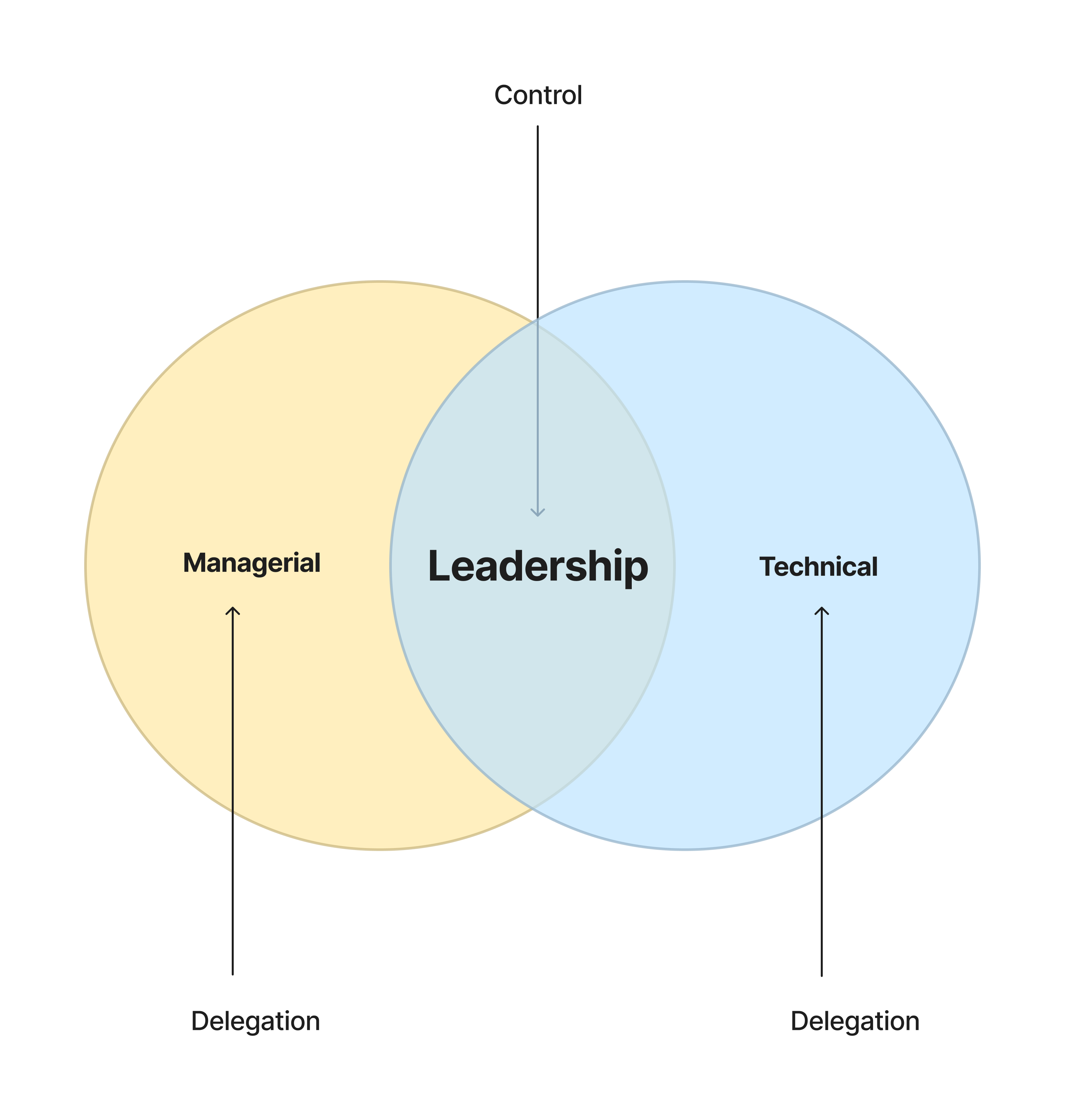

It turns out that we can use this delegation model to work out how best to manage senior staff that report to you, regardless of whether they are a manager or an individual contributor. The key is to think about the intersection between the two roles.

The Venn diagram below illustrates this:

Both circles represent the roles of senior managers and senior individual contributors. The circle on the left is that of the manager (who produces output through management), and the circle on the right is that of the individual contributor (who produces output through technical contribution). The intersection between the two circles is the shared aspect of the two roles: leadership.

Yes, leadership an overloaded and sometimes hand-wavy word that often means nothing. But what do we specifically mean by it? Let’s break it down:

- Managers demonstrate leadership by leading organizations. Whether it’s one team or a whole department, they are accountable for the output of the organization that reports to them. The responsibility of individual tasks is delegated to their direct reports, and the manager leads the organization to achieve its goals through defining the right teams, people, and processes.

- Senior individual contributors demonstrate leadership by leading technical initiatives. This may manifest in being the lead developer on a project, or being responsible for a technical area of the product. Even though they do not have direct reports, they set technical direction and are accountable for its success.

The key to managing both roles with the same approach is to focus on that intersection between the two circles: developing their leadership. This is where you should assert the most control, and where you should be most hands-on. This is where you should be coaching them, giving them feedback, and helping them to grow. It’s where you should work closely with them to ensure they are working on the right things with the right people at the right time.

What you keep within your close control is ownership of the target that your direct reports are aiming for, but you let them choose exactly how they choose to hit it. A manager reporting to you will aim at that target by constructing the right team, people, and processes for the job. Then, they’ll use their managerial skills to make it happen. Given the same target, a senior individual contributor will aim at it by assembling the right technical solution. Then, they will use their technical skills to make it happen.

Example targets are:

- Building a new feature. A manager will assemble the right team, people, and processes to build it. A senior individual contributor will assemble the right technical solution to build it.

- Improving the reliability of a system. The responsibilities of the roles are outlined as above, but the target will be key metrics to achieve such as increasing uptime, smoothing the range of latency, and reducing error rates.

- Improving the speed of a system. This time the target will be metrics such as increasing throughput, improving P99 latency, and a reduction in resource usage.

Whether you’re managing a manager or a senior individual contributor, the aim is the same: you stay hands on and control what their target is. However, the details of how that target is achieved is an implementation detail that you delegate to them.

By utilizing your management fundamentals of coaching, delegation, and 1:1s, combined with your focus on the target, you can lead both roles in the same way.

The neat corollary of this is that it encourages close collaboration between the two roles by default. For example, if an Engineering Manager and their Staff Engineer are aiming at exactly the same target and being measured on its success, then collaboration and alignment follows almost effortlessly, making everyone’s job easier.