Performance review season always gets people thinking: where am I going? Where do I want to be next year? Why haven’t I managed to get that promotion this time around? What’s the point of all of this anyway?

How do we find answers? I am not an expert in your career. But I’ve been around enough to begin to see patterns, and sometimes being transfixed on a single goal can do more harm than good. Let’s dig into this a little bit.

The Fallacy of the Straight Line

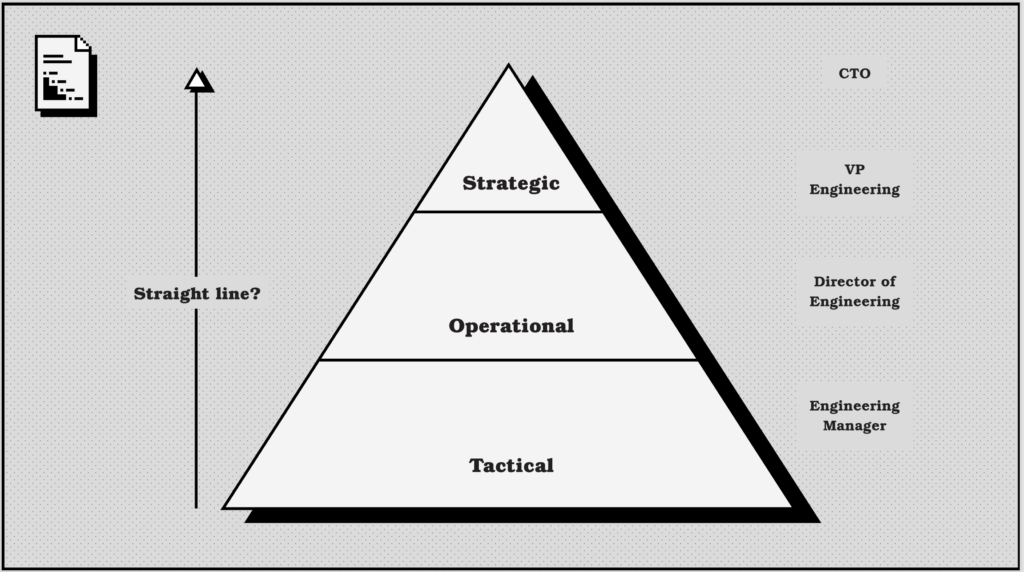

Something that often throws people off is the idea that they need to doggedly progress in a straight line. For example, if someone had gotten to the point in their career where they were leading a team for the first time, they might look upwards and think that their ultimate goal is to find the shortest path to the top. See the diagram below:

This hypothetical person may believe that the game they are playing is about going from engineering manager to director to VP to CTO as quickly as possible, else they have failed in their quest. However, careers are long. A narrow focus on getting everything yesterday can be incredibly damaging to both their mental health and their ultimate destination.

A quest for self-actualization through becoming CTO before the age of 35 can lead to burnout, disillusionment, and a sense of failure. It may also lead to a lack of focus on the things that actually matter, such as building a portfolio of skills and experiences that will make them a better and wiser leader in the long run.

And get this: the path to increasingly senior roles is not something that you have complete control over. The upper echelons of leadership, which includes senior individual contributor roles also, are a function of the skills of the person that is doing them, combined with, most importantly, the fact that the given company needs someone to do that role at that time.

Sometimes companies just don’t need someone in that position. This can pan out in a number of ways. For example:

- If you work for a small creative agency, it will likely never get to the scale where it will need middle management, let alone a CTO or dedicated principal engineer.

- If you work for a large enterprise, it may have a rigid internal structure that doesn’t allow for the kind of lateral moves that you need to make to get the experience required to get to the top. You could wait your whole life for a promotion there.

- If you work for a company that is in decline, it may not have the resources to promote you, even if you are the best person for the job; in fact, they may be trying to flatten the organization due to this period of austerity.

So, it’s often not you, it’s them. And that’s OK.

It is why it is so important to focus on what you can control, and let go of what you can’t. And it is also important to loosen your expectations of where exactly your career may end up, and instead focus on the journey that you are on right now, with a mindful eye on your general direction toward a future that makes you happy whilst developing a portfolio of skills and experiences that make you a better leader.

And it just turns out that there is an analogy that we can use to help us think about this: the Tarzan method.

Vine Swinging

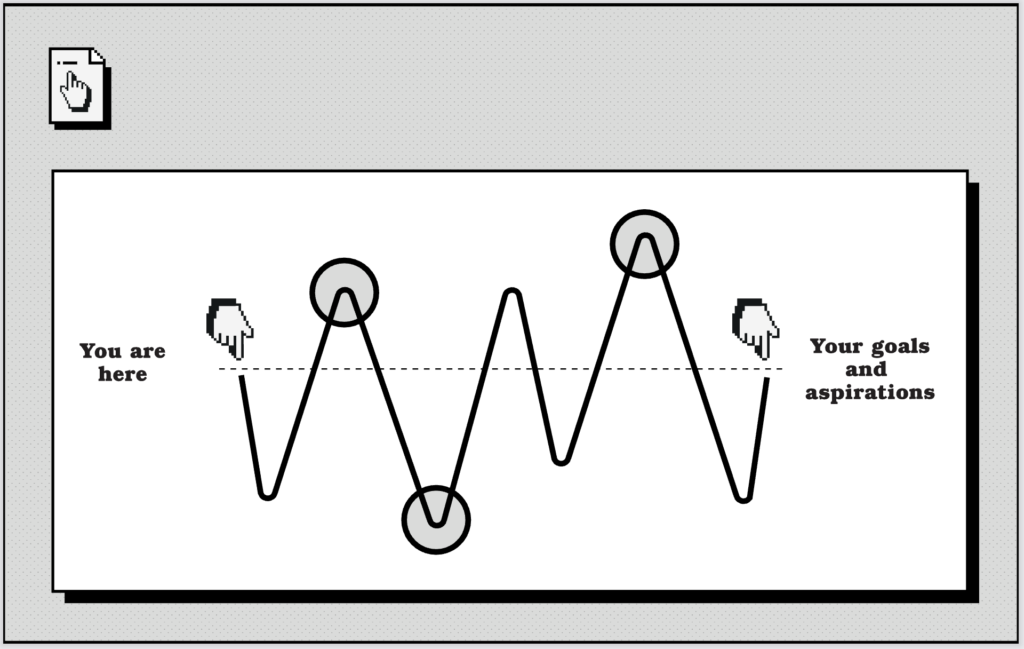

New York City–based filmmaker Casey Neistat once answered a question about the nature of his own career progression with a neat analogy. It fits in well with having a more exploratory, playful, and joyful approach to your own career. In the video, to answer the question, he pulls out a big roll of paper from the wall and lays it across his table, and then proceeds to draw something similar to the diagram below:

On the left-hand side of the diagram is where you are right now in your career. On the right-hand side of the diagram are your current goals and aspirations, whatever they may be. The dotted line that is connecting the two is an idealized optimal shortest path that you could take to get from where you are to where you want to be.

However, the problem is that this direct path may not be possible, and it may not even exist. If your dream is to be the CTO of the biggest technology company in the world in twenty years time, which is a grand, respectable dream, then how do you even plan for that? It’s highly likely that this company doesn’t even exist yet, and the skills that you need to get there may be in a field that hasn’t even been invented.

Instead, you should think about your career like Tarzan swinging through the jungle. Tarzan starts at one tree and knows that he has an ultimate destination, but the path to get there isn’t immediately clear: there are hundreds of different trees that he could swing to. He doesn’t know which one is the right one at any given time. He just has to trust his instincts and his general sense of direction and then progress to the next vine, and then the next, and then the next. In the diagram, these vine swings are represented by the up and down line that eventually connects you to your goals.

As you swing from vine to vine, those leaps will take you along a path that is unique to you. Your first swing may take you off-course when you measure yourself against the dotted straight line, but it may also take you to a place that you never even knew existed. The same is true for the next swing, and the next swing. These new and unknown places are marked on the diagram as circles at the peaks and troughs of the swings. They may even be the most important places that you visit on your journey.

And here’s the neat thing: it’s likely at these most outward swings of each vine that you discover what really matters to you. You may find that you love a particular type of work, or a particular type of company, or a particular technology. You may find yourself trying a role that you hadn’t originally considered, or trying out working remotely, or moving to a different country. You may find that you love smaller start-ups rather than big enterprises, or perhaps the other way around. Who knows what you might find? That’s the beauty of the Tarzan method.

The Trajectory of Your Swing

The Tarzan method is a great way to think about your career progression metaphorically, but it doesn’t give you a lot of practical advice on how to actually get from one vine to the next. For that, we need to think about the trajectory of your swing. A heuristic can help here: scope and impact.

- Scope is the breadth of your responsibility. It covers the size of the team that you manage, the size of the budget that you control, the number of projects that you are responsible for, and the number of people that you influence. It is the size of the sandbox that you play in.

- Impact is the depth of your responsibility. It covers the result of the work that you produce, the output of your team, the effectiveness of the decisions that you make. It is the quality of the sandcastles that you build.

If you are thinking about your leadership career as a series of vine swings, then you can think about each swing as a progression in either scope or impact, or both. Ideally, when you zoom out at any point in your career, you can step back and observe that both have been trending upward over time.

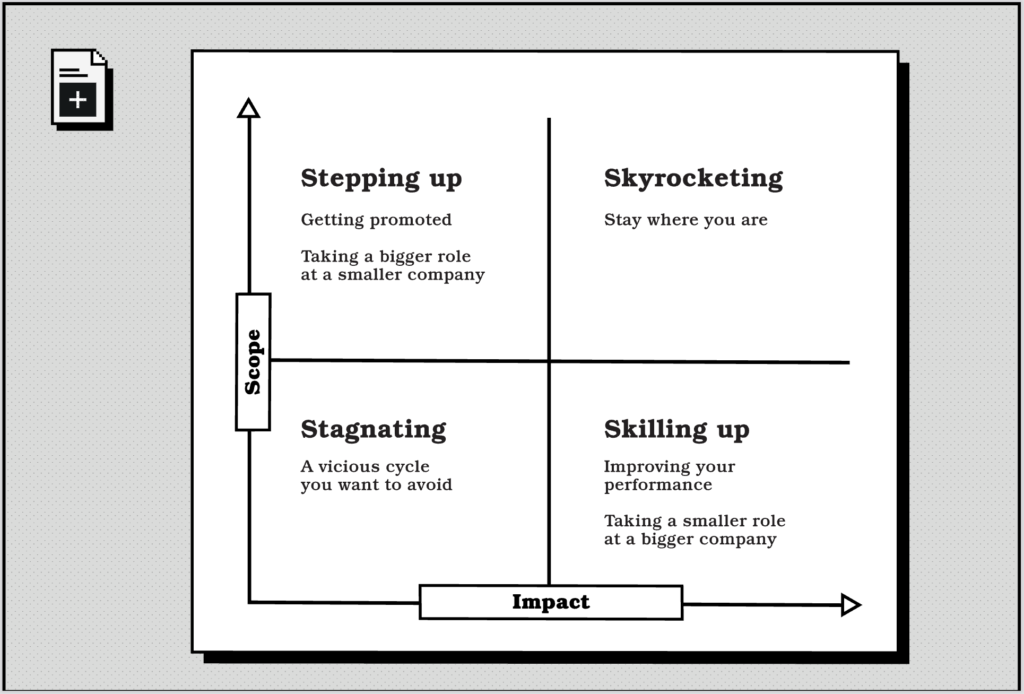

In fact, we can plot the interplay between scope and impact as a quadrant, as shown below:

On the x-axis, we have impact, and on the y-axis, we have scope. Given your own internal measurement of your current scope and impact, you can work out which quadrant applies to you in your current situation and then think about which of them should guide you in your next vine swing.

Each part of the quadrant begins with the letter S, and they are, starting at the bottom left and progressing clockwise:

- Stagnating: You have low impact and low scope compared to where you want to be. You are likely in a role that is not challenging you or satisfying you, and you are not making the impact that you want to make. Staying in this zone is not good in the long run. For you, it means that you are going to grow continually more dissatisfied with your work. It also becomes a vicious cycle: the less satisfied you are, the less you are likely to do good work, and the less opportunities that you are likely to get. You need to move out of this zone as soon as possible.

- Stepping up: You are in a period where you are primarily focused on increasing your scope so that it can lead to a larger impact in the future. The ways that this can typically happen are by taking on more responsibility, such as by getting promoted, or by taking a vine swing to a different, often smaller, company that is offering a bigger role than you currently have. You can commonly see this happen when someone moves from a bigger company to a smaller company for a more senior role, such as a director of engineering at a public company moving to smaller private company as a VP of engineering.

- Skyrocketing: This is where you are in a role that is both offering you a continued increase in both scope and impact. For example, you may be in a leadership role in a start-up that is growing extremely fast around you. When you’re in this position, the best move is to stay where you are and continue to grow with the company. This is the most desirable position to be in, but it is also the most rare.

- Skilling up: This typically follows a stepping up period where you are primarily working on improving your performance and impact through learning new skills. This can be done by doubling-down where you are and investing in your own personal development, or by taking a smaller role at a bigger or more challenging company that will push you to learn new things.

The key to progressing in your career is to continually move around this quadrant between the top left and the bottom right, hoping that you get periods of time in the top right. The more that you can do this, the more that you will grow in your career. And, it goes without saying, you don’t want to be in the bottom left for too long.

So the question isn’t “how do I get to the top as quickly as possible?” but instead it should be “how do I maximize my chance of skyrocketing in the future?” Sometimes the answer to this question isn’t to take the most direct path, but instead to take the most interesting path. You never know what you might find.

Think about it over the next six months. What vine are you going to swing to next?