Ah, the classic all-time question that has probably caused more arguments than it has resolved. The answer is, of course, it depends. However, there are some guidelines that can help you make the right decision, both for yourself and for your team.

Let’s explore.

Span of Control

The number of direct reports that a manager has is most commonly referred to as their span of control. It’s a bit of a strange-sounding term, but it’s what we have. Other terms used include span of management or wingspan.

Deciding an optimal span of control is a key part of organisation design, since it determines the relationship between the overall size of the organisation and the number of managers required to support it. If you have small teams then you’ll have more managers, and if you have large teams then you’ll have fewer.

There’s no hard and fast rule, despite what anyone says. Once again, as with a lot of writing on the internet, those who prescribe a specific number are either inexperienced or are trying to sell you something. In my own opinion, the sweet spot is around 8 direct reports. But, importantly, I’m just some guy on the internet.

The truth is that it depends on a number of factors, including:

- Practical limits. If we expect managers to do their job effectively, then there are practical limits to how many people they can manage. For example, ten direct reports could mean ten one-to-one meetings per week in addition to team meetings, individual work, coaching and mentorship, and having the flexibility to deal with unexpected issues. It’s highly unlikely that a manager could do all of this effectively with twenty direct reports. Something has to give.

- The seniority of the manager. Typically speaking, the more senior that a manager is, the larger their span of control can be. This purely comes down to their experience.

- The seniority of the reports. Managing a team of senior individuals is typically less overhead than managing a team of inexperienced individuals. The former will be more self-sufficient and require less guidance, whereas new or inexperienced staff will need more hands-on coaching and mentorship.

- A manager’s level of individual contribution. Some managers still contribute code meaningfully to their projects and therefore they may benefit from a lower span of control. Conversely, managers that delegate most individual contributor work and focus on strategy and planning are able to manage a larger team.

- The type of work that the team does. Highly collaborative teams work better with a lower span of control, since there is more inter-team communication and coordination required. Teams that manage many smaller streams of work can be bigger as they work more independently.

Span of control has been a hot topic in recent years: notably during the economic downturn after the Covid-19 pandemic. After the most bullish of bull runs came to and end in 2020, many organisations were forced to make cuts to their workforce. After companies put the brakes on the rapid hiring of the previous years, many companies were left with managers that had too few direct reports.

This resulted in a number of companies flattening their organizations during layoffs in order to increase the average span of control of their managers. Many of the lower span managers were let go or had to convert into performing individual contributor roles: clearly neither option is ideal for someone invested in their craft. The lesson here is that if an organization’s span of control isn’t kept under control, then there can be a cascade of highly negative outcomes for individuals when times are tough.

Spans and Modes of Operation

I mentioned that my own personal sweet spot is a span of control of around 8. However, I can’t claim that what is true for me is also true for you. It’s just my experience.

However, what is true is that there are different modes of operation for managers depending on their span of control. These modes of operation are driven from the practical limits that I mentioned earlier: they are less of a choice of how to operate and more of a necessity because of the span.

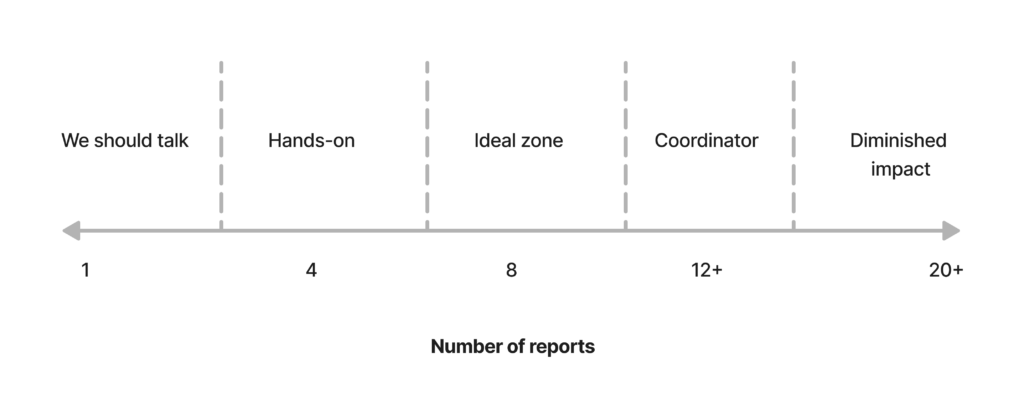

Let’s have a look at this visually.

Moving across the diagram from left to right, we can see that:

- A manager with one or two direct reports is effectively redundant in their role. There isn’t enough management work to do to keep them utilized and growing as a manager. Ideally, managers with spans of control this small should convert to individual contributor roles and have their reports fold into their manager, or they should be given a larger team to run. Given the flattening exercises that have been happening recently, you don’t want to be stuck in this position for too long: take action.

- A team that is on the lower end of the ideal range (3-6) is suited to hands-on managers. If a manager is still a strong individual contributor, then with a small team they can still contribute meaningfully to the team’s output. This configuration can work well for those that are beginning in management (they have less people while they learn their craft) and for those that are able to perform as technical leads (they have more time to contribute individually). And to everyone who strictly says that managers should not contribute code, I say that you’ve probably never worked on a small team with a highly technical and contributing manager. They exist, and they are awesome.

- The ideal mix falls in the middle of the range (5-10). This is the sweet spot for most managers. They have enough direct reports to be able to delegate work and provide support and guidance, but not so many that they are unable to do their job effectively. This span of control should constitute the majority of teams in your organisation.

- A team that is on the large side (12-15) is where management and coordination tasks dominate. A manager with a team this large becomes effectively a coordinator, and gets everything done through delegation. They’re like air traffic control. This configuration is sustainable for temporary periods of time, but you should find a solution to this as soon as you can by splitting the team.

- At the extreme end of the range (15+) is where managers become ineffective and diminished in their impact. There is simply too much going on to keep on top of. Just imagine what it’s like to do 15+ one-on-one meetings per week, in addition to team meetings, individual work, coaching and mentorship, and having flexibility to deal with unexpected issues. It’s not sustainable and you are not giving your manager the chance to do a good job. This configuration is a recipe for attrition.

With this scale in mind, you should revisit your org chart periodically to ensure that managers are performing in the right mode of operation for them, including addressing those at the extreme ends of the scale by folding or splitting teams. Do this by deciding what the ideal span of control is for your organisation, communicate the benchmark, and then work with those that are outside of the ideal range to find a solution.

It’s essential to do this to ensure that your managers and your individual contributors are set up for success.

Special People

Sometimes you may meet someone who will argue vehemently that they can manage a team of six bazillion people by either being so influential that their team is self-sufficient and driven by telepathy, or by being so incredible at their job that their two one-to-one meetings every year are like a religious experience for their direct reports.

Well, maybe those people exist. And more power to them. Maybe that works. But maybe their direct reports hated it and didn’t feel empowered to bring it up because the manager was running the company. Who knows? But really, who cares? Let those people be those people. For you: it’s simple, really. Aim for the sweet spot. It’s for Jedis and padawans alike.