There’s an exciting announcement at the end of this article, so make sure you read all the way to the end!

For many of us in the tech industry, we are either in the middle of, or ramping up into, performance review season. It may be the case that you are currently writing your self-assessment, or writing reviews for your staff, or you are preparing for calibration meetings.

But the question is: why are we actually doing this? What is the point of performance management? Why do we spend so much time and effort on it?

To understand more deeply why performance management is so important, let’s revisit some broader themes that we’ve previously touched upon in the blog:

- We covered the concept of longtermism, which is a lens that we should hold up to everything that we do, allowing us to ask ourselves whether we are acting altrutistically toward the future, even if it means sacrificing some short-term gains.

- Additionally, we considered that the speed of progression of society is an ever-accelerating function based on the ability to continually build upon the work of those that came before us. We saw that organizations that are able to continually learn become better, smarter, and more effective in the long run and that this is a key competitive advantage that senior leadership should focus on.

The philosophy behind performance management is extremely similar: we expect everyone in the organization to continually improve, and we want to ensure that we have a system in place that allows us to keep raising the bar higher and higher over time.

In the same way a human transported from 250 years ago to today would not be able to comprehend the world around them, the same is true of our company: we want the collective capability of our organization to advance rapidly under our leadership.

General Electric was founded in 1892 and is still a Fortune 500 company today. Employees from 1892 would not be able to comprehend what current-day employees do, which is a function of this ever-increasing bar of capability and performance.

As a senior leader, you are responsible for the positioning of the performance bar and for ensuring that it is continually raised over time in such a way that you are able to attract and retain the best talent. The bar last year is lower than the bar of this year, because this year’s bar is a function of the bar of last year plus the collective learning and improvement since that time.

This is a key insight, because without continually raising the bar, your organization will stagnate. Performance management isn’t primarily about checking that everyone is doing OK, nor is it primarily about ensuring that everyone is fairly compensated (although these are second-order effects): it’s about ensuring that your organization is getting better every week, month, and year.

A good performance management system typically encompasses the following elements:

- A clear definition of what good performance looks like in each role, which is typically a set of competencies that are expected of everyone in the organization. It’s likely that you’re familiar with these concepts already. If you’re looking for inspiration here, then check out progression.fyi to see examples from real companies.

- A regular performance review process, which is typically done once or twice a year. This is comprised of numerous subparts, but commonly includes a self-assessment, a manager assessment, and a peer feedback process that results in a rating.

- A calibration process, which is a way of ensuring that the performance management system is fair and consistent across the entire organization.

- A PIP process, which is a way of ensuring that people who are not performing well are given the opportunity to improve, or are exited from the company.

- A compensation process, which rolls up the performance management process outcome into opportunities for pay increases. This is typically done once or twice a year, and is often done in conjunction with the performance review process. The idea is that your best performers have the greatest opportunity for the largest compensation increases, and your worst performers have the least. This provides incentives for people to perform well and also provides a way of ensuring that your best performers are retained.

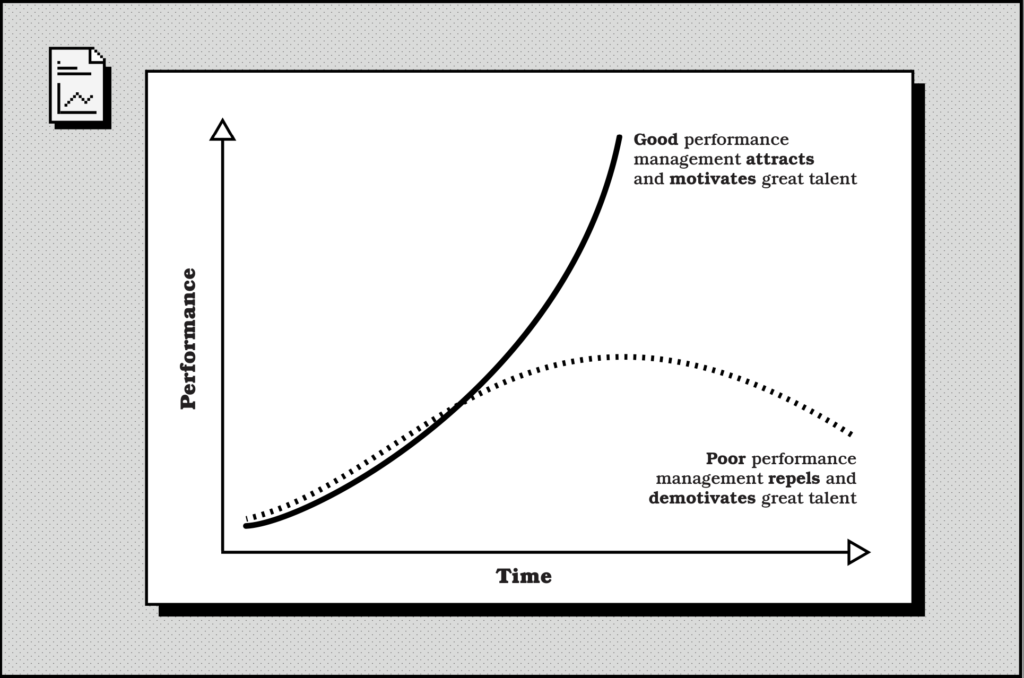

This is a lot of work, and ownership of the whole process may sit within your HR function. However, as a senior leader, you are responsible for ensuring that this process is working well, that you are leveraging it to its full potential, and that you are working with the owners of the process to iteratively improve it. With time, the effects of good performance management will compound, as you can see in the graph below.

What does this mean? It means that:

- An effective performance management system, applied consistently, positively compounds whole company performance over time. Similar to how humanity’s capabilities are accelerating through ever-improving technology and communication, so too will the capabilities of your organization. You will attract and retain the best talent, which will result in you outperforming your competitors, which allows you to attract and retain the best talent, and so on, in a virtuous cycle.

- A poor or non-existent performance management system, applied badly, negatively compounds whole company performance over time. This is because your best performers will leave, and your worst performers will stay and stagnate. You will not be able to attract the best talent because they would rather work at companies that are filled with other people who are performing well. This is a vicious cycle.

To apply a video game analogy, your performance management system is the company’s power curve. The term power curve is used to describe the rate at which the various elements of a game improve over time, such as the power of the player, the power of the enemies, and the power of the items and equipment.

For massively multiplayer online games such as World of Warcraft which have been around for decades, the power curve is continually increasing, and the game is getting harder and harder at the highest level of content. Players that have been playing for a long time have invested in their characters and have obtained the best equipment, and are therefore able to take on the biggest challenges. Players that tried the game for a few months in 2005 and then stopped playing will find if they logged in today, the high end of the game is now unrecognizable: they simply do not have the skills or equipment to compete. The power curve has moved on without them.

So performance management isn’t just about getting some adminstrative stuff done a few times a year: it’s actually critical to the long-term health of your organization. You set the power curve in a way that ensures everyone is continually improving, and that new players want to come and join your game. For players that aren’t up to the challenge, you invest in more opportunities for them to improve, and if they don’t, it’s probably best if they go and play something else.

Keep this in mind as you go through your performance review season. It’s not just about the here and now: it’s about the future of your organization.

Become A Great Engineering Leader Is In Beta!

I’m excited to announce that my new book, Become A Great Engineering Leader, is now in beta!

This book is the spiritual successor to my first book, Become An Effective Software Engineering Manager and is designed to help you level up your leadership skills and become the best engineering leader you can be.

It is especially targeted at engineering managers who are looking to grow into more senior leadership roles like Director, VP and beyond, but the topics that we cover are applicable to anyone who is looking to become a better leader in general. If you like the content of this newsletter, then I’ve been secretly serializing some of the content and improving it based on your feedback. So thank you for that!

The book being in beta means that you can buy it now and get access to the first two thirds of the book, and then receive updates as I finish writing the final third. You also have the ability to provide feedback on the content, which I will use to improve the book before it is published.

It’s been a long time coming, and I’m really excited to share it with you. I hope you enjoy it. Grab it here!

Until next time. 🚀